There were many who thought that the vote could go against staying in the EU; many fewer thought that the vote would go that way; virtually none in power – politically or commercially – believed that it could or would. As such, on both sides of the Channel, virtually no deep thinking, strategizing or planning actually took place ahead of time. The financial markets reacted as they should have, pricing in a large amount of negative uncertainty into the Pound, the Euro and many securities in both markets. After the requisite few days, the volatility subsided; this, however, did not in any way signify the storm has passed. There always are a sufficient number of risk takers who are willing to buy on dips, thereby preserving a short-term manageable range in prices. Over time, the Euro has ostensibly stabilized, while the pound has continued its free-fall, stabilizing only during October. If/when news occurs and developments actually take place, the room for extreme downside movement remains alive and well for both currencies.

And, although with Theresa ‘s announcement, the vast majority of commercial interests and now, a large number of politicos believe a separation to be inevitable, most believe it is neither in the general interest of the EU nor Britain. The only hope is that, rhetoric aside, the shambolic process seen to date on both sides of the Channel will morph into something vaguely rational. However, with the current cast of characters, it is hard to be unduly optimistic.

The result of Brexit has been an upheaval of the British political scene, with David Cameron resigning and an unexpected candidate quickly stepping in. Gove was responsible for knocking out two of the most obvious candidates, Boris Johnson (the U.K.’s Trump imitator) and himself in one of the clumsiest pieces of political argy bargy in recent history, leaving the pathway open for Theresa May. The Labor Party, showing itself more indecisive than even its most vociferous critics had believed possible in the Brexit debate, has left itself essentially emasculated. The rift between the Party faithful and those actually elected to office highlight the chaos. Thus, one of the most critical periods in British political history will be undertaken with a great uncertainty at the top; hopefully new blood will represent the infusion of sanity the UK desperately needs, but the ‘surprising’ ministerial selection and the early May positioning do not inspire great confidence.

Across the Channel, the rhetoric has just begun – with years more certain to follow; Juncker and the French have led the bloviating with aggressive posturing against making any concessions to the British. Merkel has stood behind her basic premise that you can’t leave the Union and expect a pat on the back and sympathetic wooing. The fundamental leadership vacuum in Europe (excepting Merkel) has left only the nationalist parties cooing and rubbing their hands, as they expect major gains in elections throughout Europe over the foreseeable future. Using immigration as their basis of discontent, the increase in nationalism and the concomitant seeds of racism are beginning to flourish. Of all dangers in Europe, this is the one with the greatest threat of throwing the region back into its millennia-long history of internecine strife. And, in the background, has always been a nagging concern that much of the current peace depends on the military support – financial, manpower and ‘suasion’ – of the U.S., both in its own right and through NATO. Europe, for a territory of its size, has a remarkably ineffective military. Fortunately, with the U.S. as number one ally the concern has remained buried. But will the U.S. continue to be there to the same degree? Although there has been sporadic grumbling in the U.S. over its military budget, the power of the military apparatus and lobby, together with a status quo oriented leadership (post Reagan) has resisted major cut-backs; as a result, no one in Europe has really considered the U.S. greatly diminishing its role. With the Electoral College Trumpeting in a new era, this all has the potential to change. All of a sudden, uncertainty is the new certainty. Although, Trump has been tough in his posturing, he has also been hugely erratic; it is this latter set of behavior that opens up a startling level of policy concern for the future. Leaders in Europe (and elsewhere) can design strategies to react to/handle either hawkish or dovish U.S. leadership. It is extremely hard, however, to plan for what promises to be a series of possibly contradictory and/or changing postures and policies. In poker, it is extremely dangerous to play at a table with a highly irrational player (no matter how inexperienced) who has an infinite bank to buy in.

So Europe faces some tantalizing issues. In an era of budget constraint, outside of the UK, which spends about 2.5% of GDP on military (vs. 4.35% in the U.S.), the next largest spend is France at 1.8%, with Germany at a mere 1.35%! Bluntly, Europe has leaned on the U.S. since WW2 to subsidize its defense and take responsibility for many potential threats. ICBM’s apart, Russia is much more of a proximate threat to Europe than to the U.S.; equally so, the multi-pronged Islamic kerfuffle, both on EU’s borders and within many member countries, is clearly of more palpable concern that it is to the U.S., a continent and ocean away. Action by Trump redistributing the economic responsibility for much of Europe’s military is likely to receive considerable popular support in the U.S., which should raise red flags in Europe. But what makes the situation even more problematic for the EU, is that , even were it to take on a more reasonable share of the burden, a military force requires almost complete cohesion – something virtually non-existent with the E.U. – both culturally and structurally. The massive difficulties faced by country leaders on agreeing on (let alone implementing) social and economic issues that are much less dramatic than Defense, show the daunting prospect of establishing anything resembling an effective EU military force.

The Realization – What does all this mean?

So now that the unexpected has happened, the reality has set in, relative calm has settled in, the question is where do things go from here? The hope would be that this ‘crisis’ will cause all participants to carefully scrutinize the current flaws that exist in the Euro and the structure, policies and administration of the E.U. itself. Not all those who campaigned and/or voted for Brexit are uninformed anarchists. Many of the concerns that resulted in the exit vote continue to be problems that will also influence other current (and prospective) members and potentially impair the viability of the EU as a long-term, sustainable option. These include:

- A plethora (and growing) number of different cultures, all with their own government, needing to come together to set both macro policies and agree on detailed micro issues.

- The vast gap between richer and poorer nations and limited mechanisms to responsibly bring greater parity.

- A diverse set of external borders without a single, clearly operable policy for determining how porous they should be.

- A diverse set of internal borders, with differing opinions on how open those should be.

- The difficulties of having a single currency, without having a unified central government, setting both fiscal and monetary policies.

- Having a currency, with central directives and policies that divide the participants rather than unify them.

- A head-scratching uber-bureaucracy overlaid on what, in many cases, is already a crippling underlying national one.

- The lack of implementable mechanisms to enforce policy.

There has been no shortage of opinion or commentary on all of the above and the many others I failed to include. Little has been done to address most of these prior to Brexit. Without needing to be inordinately skeptical, I can imagine that not much (beyond extensive persiflage) will actually take place on these overarching issues post-Brexit.

As to negotiating the practical terms of unwinding the official British membership in the EU and figuring out the future interrelations, there are thousands of practical and impractical details that politicians and bureaucrats will salivate over for the next decade, both for their potential historic importance and also the job security these efforts will certainly guarantee! Some issues can be parsed out, negotiated and implemented within the EU. Many others that are beyond the control of Brussels and membership in general, exist and/or will emerge from outside the Union and will impede or, at the very least shift, the efforts of EU policy craftspeople. In the end, market forces, not policy, will determine many outcomes; as is often the case, economics force adjustments faster than politicians and regulators can implement policies and rules.

There are many serious questions and issues to be addressed. It is early on in the process and it will undoubtedly be interesting to revisit many of these issues as the unwinding process evolves.

THE CORE AGENDA

Long-term Issues – What are the philosophical actual aspirations of the European Union and how can they be implemented?

- Which countries are the Union’s natural members?

- Can a multi-tiered system work, where there will always be, at best, gray areas between sovereign rights and overarching EU rights?

- How should the Union be governed?

- How should the Union be administered?

- Should there be more centralized taxation?

- What is the military role of the union vis-à-vis individual member nations, in relation to NATO and the U.N. and facing the rest of the world.

Medium-term issues – Important problems that require solutions, not equivocation

- Does the current governance structure of the Union make sense in how the agreements are written, how officials are elected/appointed and in how the bureaucracy is organized?

- In dealing with both current policies and in response to any future changes, how does one organize and fund and deploy military and police work across internal borders to deal with multi-country issues and overall EU foreign policy?

- How does one structure a system that maintains financial stability when crisis hits a weaker member? Although this should probably be listed under longer-term issues, there are several current and impending examples that preclude the luxury of leisurely contemplation.

- Given Brexit and some of the reactions this has stirred up in other member nations, what should be the mechanisms to facilitate or prevent change in membership ‘status’ going forward? The almost inevitable Brexit mess could become an unworkable contagion unless a clear set of preemptive policies and rules are developed for dealing with any other potential departing members. The current position from Germany and France is: “The stick is more powerful than the carrot.” To keep members long-term, it would seem sensible to create reasons to stay rather than punishments for leaving.

Short-term issues

- Schengen – Does it stay unchanged? What modifications should be considered? This could be considered a medium-term issue, but with elections occurring within many countries that could put many xenophobic elected officials in place, there is certainly some urgency.

- Immigration – What are the immediate policies regarding both refugee and ‘normalized’ entry into the EU? How are quotas set? How are related expenses funded? Is enforcement a national or supranational responsibility? Once again, this needs to be looked at both in the longer-term perspective and the immediate, given the large number of recent and potential immigrants.

- Internal security – What further steps need to be taken to strengthen cross-border cooperation in both preventing and reacting to terrorist activity and also in dealing with domestic civil unrest.

- How dominant does Germany intend to be in setting and enforcing policy?

- What will be the posture in dealing with the UK in the Brexit unwind?

CONCLUSIONS ON BREXIT

Brexit came as a real shock to many insiders, if not most. Many were incredulous that a decision of such long-term significance was not being made by the democratically elected representatives whose job it is to make these difficult decisions. But this was nothing in comparison with the appallingly bad communication and dissemination of misinformation to the voting public perpetrated by politicians and the media for their own petty short-term gains. Whether the UK should have remained or not, the process by which this historically significant decision was made was unforgivably flawed. This does not necessarily mean however, it was wrong.

The UK was faced with a rather challenging dilemma. Do we remain as part of an organization that is fundamentally flawed and that might suffer a significant downward spiral, but that is ‘too big to fail’? Or, do we go out on our own and see if we can replicate the resilient British spirit that kept the small island nation at the forefront of global politics for so long? This is most likely a case of choosing the lesser evil.

Nonetheless, I believe the UK has squandered the opportunity to increase the value of an extremely valuable call option. They already have the huge advantage of an independent currency; they also have a range of concessions versus other full-fledged EU members. Their relative financial health, their position as the financial center for the ‘bloc’, their significant military capability and their ‘special’ relationship with the U.S. make them very valuable to the EU, both short-term and longer-term. Used properly, this could have (putatively, still could) provided considerable bargaining leverage to gain certain concessions if they stayed, while still retaining the ultimate card of being able to leave. Why should one fold a hand, when one has a free turn of the cards? Dwelling on incompetence, however, is irrelevant.

From here on, it is a question of both negotiation and implementation. The pre-posturing on the negotiations has been ham-handed on both sides and not an optimistic indicator for the process. The parallel bureaucracies that need to be created on each and put into effect on each side of the Channel are a daunting prospect, particularly given the lack of effectiveness of many of the existing bureaucracies! On the positive side, it does generate employment!! Handicapping the outcomes is, unfortunately, impossible. In the end, possibly even more important, is the fact that outcomes are not fully determined by the governments on either side of the Channel. The markets will have their say and influence, as will other players in global geopolitics (please see the follow-up thought-piece for an intriguing scenario). The only guaranteed winning demographic is the press. What a field day for years to come…

But Brexit and the EU do not live in a vacuum. The decisions and actions being contemplated have massive direct and recursive effects on every corner of the globe. Targeted consequences are many, unintended ones virtually infinite. The next part of this thought piece looks at Brexit not as an isolated process but as a potential catalyst for much a set of much more global realignments.

CHALLENGING CONVENTIONAL WISDOM.

POTENTIAL GLOBAL REALIGNMENT POST-BREXIT

History is a constantly shifting set of alliances, allegiances and enmities. There is never a question of permanence, merely the degree of evanescence. Because changes often occur over a longer span than an individual’s lifetime, each generation, relying on its own set of lived experiences, believes it is able to create a new paradigm where extended stability is possible. And yet, history has to date, proven this to be an illusion. Humanity drifts from one crisis (i.e. critical juncture or turning point) to another. Wars, health crises, climactic disasters line up alongside the rise and fall of leaders, demagogues and the shifts in demographics and technology to see the constant restructuring of geopolitics and redrawing of borders.

Whether Brexit ends up actually being a catalyst to a major geopolitical shift or not, it certainly could. Many would like to merely see a slightly modified status quo; after all, there is comfort in incumbency. Those in power are almost always reluctant to cede or even diminish their hold and their advantages. And so there are many constraints to change – now as always. Sometimes this is good, sometimes bad. We live in a world that for a long time has been dominated by the Northern Hemisphere and the Western latitudes. This Euro/American hegemony has been challenged post WW2; some changes have occurred both within the privileged community and outside. The most seismic developments have been the rise of China and the overall economic power of Asia as a whole. The relative increase in affluence of other regions, such as Latin America, partially as a result of a prolonged commodity boom, has also been very important. The vast flow of Petro-dollars and incoherent policy by developed nations has created homes for radical Islam spanning Africa, Europe and Asia. Although there has not been a major global war since WW2 or a major global political division since the fall of the Soviet Union, there have been numerous regional conflicts and a number that fester and grow around the world today. These are unlikely to disappear or become more benign.

Regardless of the direction of any one of the current (or unanticipated future) conflicts, the simple fact is the demographics do not favor the incumbent power base. Both existing population base and birth rates outside the most developed nations make retaining a sustainable edge for the currently privileged hard to envision without either military action or a massive shift in global alliances. Instead of evaluating the potential for calamitous military engagement, this piece will explore a set of potential new alliances that could rebalance global geopolitics and economics. Naturally, the likelihood these occur in their entirely is zero; however, some elements bear discussing in the halls of power in capitals around the world.

The discussion is divided into four sections:

- A dramatic gambit by Europe as a reaction to Brexit.

- An equally unexpected strategic expansion by the UK.

- A response by the U.S.

- A reaction by China.

TERRITORY 1 – The New EU

A World-Changing Alternative – have Russia become part of the ‘New’ EU. I posit this as a paradigm-shifting and potentially viable alternative, although the long rivalries, suspicion, nationalism, etc. make it highly unlikely. The theory is based on a combination of economic, military and personal interest and exists only because of the personalities of the leaders sitting in the two pivotal seats and the relationship that exists between them. Without Angela Merkel and Vladimir Putin this combination would most likely be unimaginable. A private, unpublicized meeting between the two of them in one of Putin’s dachas somewhere in the world could rock the world. Here is a suggested monologue by Merkel:

- Vladimir, we both know you are a very smart man; you understand Russia is facing what is almost certainly a no-win longer-term situation. You run a country, with a large, well-organized military, with great weaponry; however, you face the ultimate challenge – an exceptionally long border, with hostiles or potential hostiles along most of the periphery, with insufficient ground troops to be able to deal with problems simultaneously on multiple fronts. And, Russia has a terrible demographic – a population of less than 150 million, a low birth rate and a low life expectancy. Obviously, you could always press the red button, but that would not make you the winner, only everyone a loser.

- Your country is still largely a one-trick pony, based on huge resource reserves, but this makes for instability when large swings occur, as they have over the past couple of years. Given Russia’s ‘track record’ in the financial markets, foreign capital infusions are not dependable and are likely to dry up most at times of crisis, when you need them most.

- You have a remarkable ability to ‘message’ to your compatriots and gain support for positions you wish to implement. To this point, it has worked well for you and you have had support for your approach in Syria and the Ukraine; however, eventually, if the economic situation in Russia does not improve, you might run into more difficulties. It would appear that your longer-term options might be narrowing to some degree.

- You have been able to amass an immense ‘family’ fortune, which many estimate at $300 billion to $1 trillion. Whether these numbers are accurate or not, the actual amount is still enormous by any standard, so large in fact that it might be difficult to monetize much of it, were an international effort undertaken to block you.

- The EU exists to create a trading block that can compete effectively economically with the U.S. and China and which can help provide geopolitical stability to the region. With the loss of the UK, we have lost some of this strength. However, if Russia were, over time, to develop an ‘affiliation’ with the EU, we would jointly hold an extremely important economic, resource and geopolitical position in the world. Following are some of the advantages you might consider:

– Your biggest medium-term actual defense threat is China; they have an immense army and also a huge arsenal of tactical weapons. Affiliating with the EU, makes aggression on their part much less likely.

– You continue to be threatened by NATO, of which the EU is the most proximate landmass to you; being part of us, would allow you to more effectively deploy your military resources to other areas. Our combined forces and armaments would instantly propel us to the most potent global military defense force.

– As with us, you face a major (and growing) threat on the radical Islamic front. Like China, they have a population base of military age that is difficult to confront alone. A true ‘cooperation’ would enable a better global set of solutions to an issue that is unlikely to simply disappear on its own.

– You have a well-educated work force, but the structure of your economy, markets and politics still retain strong residual impediments from the Soviet days; this is likely to dampen your progress relative to other areas in the world, particularly if you continue to require a large part of your GDP to be spent on Defense. You have seen what I have accomplished with East Germany, in gradually raising their standards of living, productivity, etc. and also in starting to remediate ecological and other issues. Were you to become affiliated with the EU, you could benefit from our expertise and economic power to strengthen your economy. Our benefit on this front – so you understand our self-interest, are: a huge new market for our products; better access to natural resources (particularly oil and gas) that could lower our current dependence on volatile regions around the world; and, a gradual affiliation with a potent military apparatus. It would also make us more long-term competitive vis-à-vis the U.S. and China.

– I could work behind the scenes to assure that many of the assets you have personally acquired remain with your family.

- I understand the public relations difficulties of achieving this plan. The ‘dominant Russia’ remains a unifying image for your country, and understandably so. However, the exact same issues exist for the U.K., France and Germany. History continually realigns borders and the players change. None of us is the same as we were. What I am proposing is a quantum shift going forward, that puts Russia in the heart of an alliance that will clearly be a global super-power. It also does it in a way that not only avoids war but, could effectively promote peace. Please understand, this proposal will, in many ways, be even more difficult to achieve on my side, given the number of different countries and different forms of democracy currently existing within the EU.

- We will carefully orchestrate a plan where I quietly build a supporting group of countries, using both the carrot and the stick; I will probably need to start with the smaller countries which most require Germany’s support; with a meaningful group, I can then work on the larger, potentially more difficult areas. At the same time, you can start to plant seeds at home. We can ‘stage’ fights and resolutions that show an ability in the press for us to work together; we can also promote trade, cultural and other arrangements that can be publicized in a way that softens images both in Russia and the EU.

World history changes only when visionary leaders take the helm. It often occurs through war or stems from crisis. The idea of bringing Russia into the EU fold would be a diplomatic tour de force by two very powerful leaders and would be a significant step in averting WMD use and resetting global power balance in a largely peaceful way. And best of all, it originates, not out of a full-blown crisis, but as a result of more tractable economic and social problems in both Europe and Russia, with Brexit being the immediate catalyst and ‘opening’ for discussion.

TERRITORY 2 – The New U.K.

With or without a Russian alliance within the EU, the U.K. finds itself in rather a precarious position. Since WW1 the U.K. has seen its global influence falter dramatically. The costs of WW2 (both economic and human) brought a rather bleak period in the U.K. through the 1970’s. Five things led to a spectacular recovery – at least on the surface:

- The discovery and exploitation of North Sea oil.

- A Thatcher-led move towards free markets and lower taxation that encouraged the growth of some post-industrial businesses, particularly in the financial service arena.

- The favorable tax environment for extremely affluent foreigners.

- The growing hegemony of the English language.

- Joining the E.U. and becoming a magnet for young European professionals, skilled artisans and workers of all types.

These all combined to bring the U.K. back to the forefront and to create prosperity in London and some of the Home Counties, as well as a few other cities around the country. However, one does not need to dig to deeply to see that although improvements have occurred further to the North and West, the levels of unemployment and income inequality remain very high. The revenue stream from North Sea oil has been largely depleted, not ‘saved’ and invested separately on behalf of the country and its citizens; and, the risk of severe economic retrenchment in the event of a financial sector crisis or general financial crisis is not insignificant.

A distancing of the U.K. from the E.U. is almost certain to result in a ‘repatriation’ of certain types of jobs to the Continent and the level of economic interaction remains uncertain. There is also a growing possibility of a full devolution by Scotland, which remains strongly pro E.U. This all leaves the U.K. very vulnerable. Nonetheless, it does retain some key strengths:

- A legal and financial system that is largely trusted around the world.

- Enterprise management skills that are globally accepted and used.

- An independent currency.

- An environment in which it is largely safe to live and is prized by many around the world.

- A meaningful military presence and a key seat in global political organizations.

- Favored relationships, stemming from its colonial past with many nations.

Although the population of the U.K. is respectable at about 65 million (including 5 million in Scotland), it is clearly not large by long-term global geopolitical standards. As part of a European grouping, it was an important part of a significant population and landmass; alone, it really is an orphan – too large to be mono-focused like Singapore, to small to really matter. Over time, demographics normally end up being the decisive factor. For the U.K. to prosper over the longer term, it needs to affiliate. An obvious choice would be to tighten the relationship on all fronts with the U.S. The clear benefits are a shared language (almost), history and the reality of having been close allies for a century. The disadvantage is the obvious imbalance of power. The UK would be destined to a similar fate as the Liberal Democrats (vis-à-vis the Conservatives) in parliament.

A more intriguing alternative would be to take another look at history and reconstitute – on vastly different terms – a portion of the Commonwealth. If the U.K. were to ally both on an economic and military basis with India (perhaps the other countries of the Subcontinent), Australia (and New Zealand) and South Africa, the agglomeration would represent some very potent characteristics:

- A major population group with overall positive demographics.

- A large percentage of the population with below global average GDP – allowing for significant growth capture over the short to medium term.

- A strong resource base.

- A very strong military.

- A very interesting geographic diversification.

- An ability to attract others into the union over time.

- A generally aligned operating philosophy (i.e. Democracy)

- A longstanding cultural understanding.

Needless to say history also comes with its negatives. The yokes of the colonial era and the hard-fought independence would not be easily shed. However, the idea, similar to that of the E.U., of a confederation of equals could hold distinct appeal, particularly given other changes in the global power dynamic. Also, given the significant differences in competitive advantage, the benefits each brings to the table would lead to a better chance of internal power balance.

For India, the largest appeal would be a more efficient access to and deployment of capital. Improving the legal system, lowering corruption, improving infrastructure and education could put them in a position to actually realize the goal of competing with China; and, without the one-child policy, ironically, India is in a better demographic position to generate sustainable long-term growth. Furthermore, a joining of military forces would help India over the longer-term, given its extensive borders with potentially hostile neighbors.

For Australia/New Zealand, the ties with the U.K. are already extremely strong. The shifting of their major export market from China to India would, most likely, be favored by the electorate, given growing concern over the level of dependence the country has on China. Also, China’s growing military is likely to be of concern to Australia and a strong pact with the U.K. and India would solidify their position.

As to South Africa, they could probably benefit the most from a close alliance. Although they remain the least dysfunctional country on the continent, their problems are massive and growing. Their emergence from Apartheid has certainly removed a yoke of oppression, but the day-to-day lives of much of the population have not dramatically improved. Crime is endemic, infrastructure in most of the country not close to keeping up with demand, their borders with neighbors quite porous and corruption ubiquitous (particularly within the ruling ANC). Furthermore, the massive lack of stability on the African continent represents a constant risk. China’s growing influence in many countries is also viewed as potentially pernicious.

Needless to say, knitting together this alliance with its disparate geography, varied politics, ideologies and character would be a challenge and, perhaps unachievable. However, with a quantum shift in the global map, this grouping could become compelling. It would also position the group well to attract significant other ‘independent’ countries who could find membership attractive.

TERRITORY 3 – The U.S. Co-Prosperity Sphere

To the extent a move is made towards a European/Russian merger and the U.K expands, the U.S. is left few choices. Initially it could and, almost certainly, would use its enormous wealth, influence and military to block these moves. However, were the will strong enough in the other two blocks, the U.S. would be in no real position to do so, without resorting to the type of actions that run counter to the entire raison d’être of the country. With a hawkish military and an aggressive, but inexperienced leader like Trump, an aggressive approach should not be ruled out; however, our recent military experiences in the Middle East have not been popular. Although running counter to a central sound bite in the Trump campaign, a much more practical approach would be to enhance the trade alliance that is already in place – NAFTA. To this point, it has been a trade pact, but could easily become much more meaningful. Combining the Super-power position of the U.S., with the resources and natural geographic barrier of Canada and the population of Mexico could act as a strong counter to the other two new groups. Furthermore, in spite of the idea that Mexico is taking jobs away from us, having a closer alliance that enhances the market to the south is more likely to add strong jobs here and solidify our ability to fill lower-end positions that Americans simply don’t want to do (agricultural, etc.). Adding Brazil to this mix, would be both a strong population, demographic and resource play and the geographic positioning would most likely lead to other Latin American countries wanting to participate. Finally, with a consolidation of power groups, Japan would be too small to remain independent. Their strained relationship with China is probably irreconcilable, in spite of geographic proximity and an important trade relationship. As a last resort, they could also want to be part of the U.S. Bloc. Their terrible demographics and limited military make some form of alliance critical if they don’t want to be absorbed into China over time.

Canada enjoys its current position of neutrality to the north of the U.S. Its proximity and cultural similarities to the larger population base to the south make a union natural, although resistance is likely to be high. Also, with its historic ties to the U.K. – the Queen is still officially Canada’s monarch – there could be a pull to join the new Commonwealth. However, given geography and the depth of economic ties, the U.S. is the natural choice.

Mexico’s politics have improved over time, but they still remain messy. The economy is the same, as is overall infrastructure. From a practical point of view, an even closer alliance with the U.S. would almost certainly benefit the country. The ability to access and deploy capital on infrastructure could help considerably, as could process management. A decrease in corruption and more consistent legal system would add stability. A population emerging into the middle class would be a great market for U.S. products and the demographics are favorable with good growth and youth. Its geographic position as a bridge to South America is also strategically important.

In a world without official blocs, Brazil is well positioned to thrive independently. It is the world’s fifth largest country, both in size and population. It has abundant resources and strong demographics. The country’s biggest problem over time has been a lack of strong leadership. This has allowed corruption to thrive and has held back economic and social development. Brazil has for a long time been the ‘next’ great country. With the recent extended China-driven commodities boom, it looked like Brazil was poised to make the leap; however, the lack of effective allocation of capital and the leadership vacuum has held the country back and its progress is currently being eroded. A full-fledged alliance with the U.S. could provide significant mutual benefits. It is never easy to extirpate an entrenched incumbent, but Brazil’s open press and frustration with its problems could provide an impetus to do so (or conversely to resist). Nonetheless a strong trade compact could strongly benefit both sides. With Brazil and Mexico part of the group, it would be hard to imagine other Latin American countries not joining or ending up in a position of ‘favored’ neutrality.

Although Japan’s GDP has continued to grow, it has been losing ground steadily to Germany, and given demographics this trend is likely to continue/accelerate. Japan faces a true crisis of identity over the next several decades. A country of great history, culture, wealth, education and productivity, its small geographic size, lack of domestic natural resources and reverse-Malthusian demographics and virtually non-existent military are bad signs for its long-term role in global power brokering. Since WW2, there has been a love/hate relationship with the U.S. This is infinitely better than the multi-century ‘tensions’ with its huge neighbor next door. A carefully crafted alliance with the U.S., as distasteful as it might be with the population overall, would most likely be the least bad alternative for Japan. The greatest antipathy would certainly come from the 50+ demographic, but their influence will start to decline and the cultural gap between the younger generation and the U.S. is far smaller. A truly bilateral trade agreement and a well-conceived joint military would almost certainly benefit both sides. The same would be true with South Korea and, with different leadership, the Philippines.

In the Middle East, the U.S. would like to keep Saudi Arabia and Israel in its fold and expand influence if possible. Although Iran should be a natural ally, this is certainly not on the cards for the near future.

Like the U.K., the U.S. has a history of cobbling together alliances to ‘preserve global stability’ and/or to promote self-interest. These blocs are inherently unstable and unlikely to be engraved in granite for ever and a day, but groupings that have balance and well-conceived sharing of influence do have a better chance of surviving than propping up and/or installing demagogues into a region.

TERRITORY 4 – China Evolves

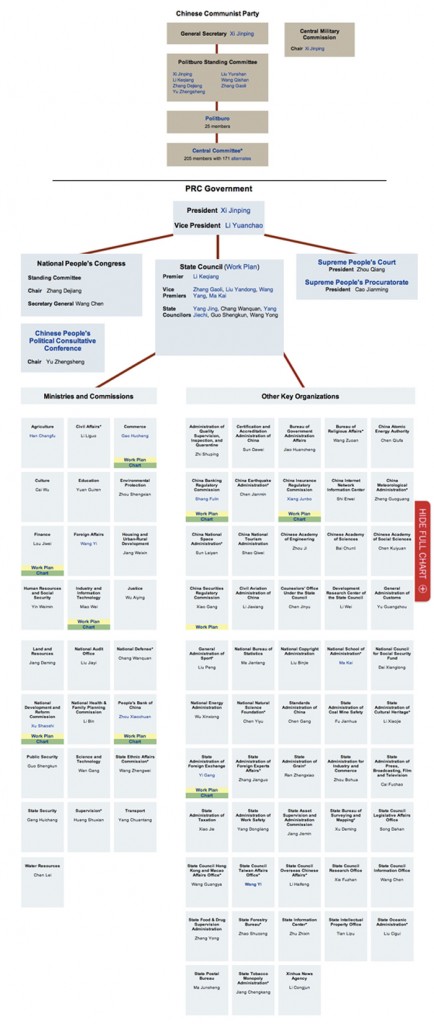

Emerging from a disastrous period of ideological tyranny and massive self-induced devastation, China has been the most important global factor to emerge in the last century. The pace of its economic development (and to a somewhat lesser degree social change) has been breathtaking and virtually unequalled in human history. The current outcome was certainly not predicted by many during the Long March of Mao’s leadership. It has brought about some spectacular gains in standard of living for a vast number of people; it helped the global economy expand in unpredicted ways; it has changed the map of global geopolitics. Needless to say, not everything has been smooth, nor has everything been positive on many fronts. China finds itself in an interesting position. The fact it has a centralized and often authoritative government has enabled it to execute plans that would have been inconceivable anywhere else in the world. It has carried along more than a billion people in geographically dispersed areas that have vast cultural differences – sometimes with a carrot, sometimes with a stick. It has granted fiefdoms – both political and economic – allowed (and perhaps encouraged) graft and corruption, so long as it fit within Beijing’s overarching goals. As a carrot, it has lavishly rewarded those who have outwardly been willing to toe the party line. More importantly, however, as is now quite evident, it has been a way of amassing considerable ‘evidence’ against virtually every official and businessperson in China, to be used when considered advantageous to further party the leadership’s agenda. The legal system used to be opaque and clearly a tool for those in power who rarely publicized anything but the results of a case and the fate of the defendants; now, there are now clearly written and often well-designed laws covering a vast range of issues and trials of public officials and businessmen are often open to public scrutiny. Why? Because, the defendants are actually guilty, by any standards! The laws exist; however, they are only selectively enforced. The government broadly allows and documents illegal activity; in most cases, when those involved properly toe the party line or don’t otherwise get caught in political or media crosshairs, this ‘data’ remains securely locked away. This, in the short-term, is likely to be very successful tactic for maintaining ‘discipline’ and keeping real power centralized. Over the longer-term, however, it is less likely to be successful, as the complex interaction of domestic and international markets, politics and information dissemination, make systems anchored on corruption and coercion virtually impossible to sustain.

Returning to the main theme of this piece, the global jigsaw puzzle. What does Beijing want to achieve. Growth, to this point, has largely been internal. International growth has been economic and China has economically ‘colonized’ a number of resource-rich countries, particularly in Africa. Going forward, in a scenario of far-reaching global alliances, what would be China’s most effective play?

So, what are those policies in the event of power grabs by the constituencies discussed above? Given China’s increased wealth and power and its large population, it is hard to conceive the leadership remaining passive, while the rest of the world consolidates. But, who are China’s natural allies and/or targets? Frankly, there are very few culturally compatible allies. In the region the most obvious are: North Korea and Taiwan (after an immense amount of hand-wringing, posturing and play-acting); Indonesia; the Philippines with the current anti-U.S.A. president also represent meaningful and geographically reasonable affiliations; somewhat further afield and for completely different reasons, Iran and Pakistan are intriguing possibilities; Any resource-rich dysfunctional African nation, with a kleptocratic leadership could fit the bill; and, perhaps a disaffected Latin American nation.

The problem with this type of alliance is that China’s centralized control-dependent, ‘iconic’ leadership model is culturally anchored. It doesn’t necessarily play well in other countries; in fact, in many countries that also have a ‘strongman’ approach, the idea of two strongmen is hard to conceive. In order to have a global alliance, China would need strong enforcement mechanisms. They have the population and the capability of building a military to do this, but a world of trade and cooperation runs counter to this approach, leaving most of the countries listed as either independent or seeking other affiliations.

CONCLUSION

As you can probably surmise, growing up, I was an avid player of the game Risk. Looking at the relative strengths and weaknesses of countries and larger geographic areas has always been fascinating. As with any hypothesis, the ‘theory’ outlined above is obviously extraordinarily unlikely to come to pass. History, if not random, is certainly unpredictable. The virtually infinite number of variables and the ever-changing complex skein of global politics make prediction virtually impossible – look no further than the Brexit and U.S. election results.

In looking at the globe today, as always, there are areas of clear change and instability. Most are local; some are global; others risk crossing borders. And, as at any other time, there are affiliations, allegiances and enmities. But these will continuously drift, as sands in the desert. Why?

- New leaders

- Demographics

- Wars

- Technology

- Natural causes (weather, health, etc.)

The shifts are normally messy and most frequently involve power plays and massive death/suffering. They are rarely in the best interest of the ‘people’, merely expedient for those with the greatest relative power at the time. In spite of the growth of trans-national organizations like the United Nations – the primary mandate of which is to prevent global conflict – these will almost certainly fail when confronted by ruthless policies by the strongest member(s). Realism is often confused for pessimism, but primarily by optimists! The theory of having four power blocs, with each being self-sufficient and able to generate ongoing economic and social growth is a potential way of avoiding armed global conflict. Furthermore, each would not operate in a vacuum. There is huge benefit to trade and other forms of cooperation. A balance of power among four groups, each with strong capabilities and comparative advantage, is most likely a better balancing mechanism and deterrent than a single or pair of super-powers. It is also positioned to be much more effective at ‘policing’ than either an individual nation or a discombobulated babel of bickering (aka the UN). Globally dislocating issues, such as the radicalization of Islam, the growth of ‘rogue’ states like North Korea, the export of pollution and other long-term negative externalities could possibly be better addressed.

Naturally, many nations and a large percentage of the world’s population do not figure directly into this four-bloc model. Over time, some countries might choose to affiliate, be involuntarily subsumed or simply remain independent. But that is not central to this discussion. The real key is whether the combined threat to European unity as a result of Brexit, Euro dysfunction and massive internal political tensions within many member countries could be a catalyst to global strategic realignment. The most likely answer is no. It seems most probable that everyone will muddle on. Europe will decline in relative strength, but as the world’s third largest economy, they will still remain a force to be reckoned with. I still register concern that the growth in political and social instability might pass the point of muddling inflection and escalate into serious conflict. As to the UK, the combination of having Sterling, being a global financial center and having a close allegiance to the U.S., makes it hard to see a ‘disaster’ scenario; on the other hand, it also seems hard to see a massively positive outcome either!

As always, I welcome any and all feedback and comments both factual and opinions. Thank you for having had the patience to wade through this tsunami of verbiage!