INTRODUCTION

It seems no one today around the world is without an opinion about China and the Chinese.

- They are stealing our jobs

- They are bailing out the West

- They are destroying the planet

- It is unbelievable how fast they have left Maoism behind

- It is incredible how much power the old-guard Communists have retained

- They are putting out PhD’s at an unbelievable rate and are moving too fast up the ‘food chain’

- Their need for critical high-end input items creates opportunities for everyone

- Their human rights record is horrendous

- They have opened up to outside influence more intensely than anyone could have anticipated

- They have transitioned towards a market economy at breakneck pace

- Real power has been retained in the old SOE’s and among a selected elite

- China represents the greatest military threat to global stability

- China represents a potential balancing foil to U.S.-based military hegemony

These thoughts address only a fraction of the areas in which China touches the world on a daily basis. As an outsider, with no actual current engagement in the region, but with a history of travel and related business activity, I find it very interesting how analyses on the region – its politics, economics and social trends – tend to be either grossly over-simplified or conversely, extraordinarily over-complicated. This piece is designed to provide an overall framework for viewing critical issues currently confronting China, its leadership and its people. There is unlikely to be any aspect that is new or revelatory – the goal is simply to bring together and organize in a readily digestible format, some knowledge from a diverse group with knowledge of and experience in the China of today.

The paper will be divided into five sections:

- How China has reached its current position – a brief synopsis.

- Internal and external issues confronting China’s current leadership.

- How the current political system actually works and why centralized control can survive.

- What needs to happen to enable China to be a long-term globally interactive superpower.

- Overall conclusions and recommendations regarding investment and business activity by foreigners in China.

China – a Brief Synopsis

China has one of the longest documented histories in the world (with written references extending back at least to the Shang Dynasty (more than three and a half millennia ago) and has at various times been a leader in areas of military, politics, literature, art, cuisine and essentially all areas of human endeavor. Over the centuries and millennia, it has brought together a host of different cultures and ethnicities and has had a large population relative to other extant cultures during most periods. Governing structures have varied, depending on the dynasty, with many being centralized. However, given the geographic dispersion and the lack of ready transport (even today in some regions), there has most frequently been either explicit or de facto regional and local control. Nonetheless, in order to keep unified the rambling diversity that was and is China, expression of power has needed to be manifest. Rebellion and dissent have been handled ‘firmly’. Today, in spite of the global press’ focus on acts of repression (particularly in regions such as Tibet), this has been a period of almost unparalleled restraint in terms of military and police action within China’s borders. Given the pace of change in every aspect of Chinese society, this restraint is actually remarkable.

To outsiders, observing the evolution of Chinese geopolitics, the country can appear schizophrenic vis-à-vis foreign relations. China has had periods of strong external trade and communication and others of state-fostered introspection/xenophobia. However, this has largely reflected either perceptions of political exigency, or the personality of the emperor at the time or both. Some ascribe isolationist policy to an inherent genetic trait – a China ‘gene’. Yet, two things would bely this criticism:

- The diaspora of Chinese emigrants and exiles across Asia (and the world) and their relative level of success in widely differing cultures; and

- The fact that during periods of historic strength (e.g. the Tang and early Ching Dynasties), China did reach out either in forms of trade or military activity.

Regardless, the swing of the past couple of decades from a hugely isolationist policy, with aggressive external conquest the main form of international communication, to a relatively militaristically benign (at least on the surface) approach with massive trade and global communication is truly extraordinary; to many of us studying China over years, virtually inconceivable.

Absolutely nothing is absolute! The U.S. most frequently, but colonial powers in general, are accused of ignoring context. Everything is seen and must be analysed through a specific lens. Therefore, use of force by the U.S., U.K., Germany, France, etc. is viewed as necessary and justified to preserve global democracy, while actions by Iran, the ex-Soviet Union, China, etc., merely as a form of self-serving aggression designed to destabilize the world! There is much to be said in favor of varying gradations of democracy, but the context and application is extremely important. Most of the countries espousing a broader dispersion of power went through periods of massive instability, often lasting more than a century, as they shifted from agrarian to industrialized urban societies. This often resulted in wrenching civil wars, considerable bloodshed and this frequently occurred in nations with relatively homogeneous populations and often constrained borders. The issues facing China have not been limited to mere industrialization, but also reflect major issues of population, infrastructure, food production, health, etc. Attempting to conveniently squeeze Chinese politics of today into Western policy pigeonholes is naïve at best, patronizing, unrealistic and dangerous at worst. Please do not take these statements as those of an apologist for actions that are often not long-term productive or even acceptable – merely as reflections on a group of very focused bureaucrats/technocrats, trying to achieve centuries of change in mere decades, with the expected concomitant error rate.

In China, democracy has never been the operative system nor (until recently) even a highly debated concept. The Chinese consider democracy an individualistic paradigm, whereas the overarching ethos of China is that of a gregarious society, where the group is more important than the individual and order needs to be maintained (at whatever cost) to provide stability and progress. The country’s geographic position and geopolitical evolution have made sustainable control the policy cornerstone. China has faced a myriad of threats from outside and equally intractable issues internally, including the practicalities of feeding and controlling a large, dispersed population, with huge infrastructure challenges. Even in comparison to an often brutal past, the 20th century represented a particularly harsh and challenging period for China and most of the Chinese people. It began with a weak Ching dynasty that saw strong foreign incursion, followed by Civil War between the Nationalists and Communists, then an appalling occupation by the Japanese and culminated in the brutality of the Mao Dynasty (during which it is estimated as many as 80 million died, either through military campaigns, murder/death in incarceration or policy-induced starvation and/or healthcare privation). These decades saw not only the repression of a highly skilled and cultural elite, but a complete stagnation in the education of at least two generations. For 26 years there was extraordinarily brutal control that effectively stifled any form of dissent, independent communication or progress. The Communist Party’s ability to clamp down and stifle any form of unsanctioned press and to prevent the dissemination of any foreign media, dramatically enhanced the effectiveness of their propaganda machine. To those of us in the West during the 1970’s, it would have seemed inconceivable that there would be any form of rapprochement during our lifetimes. It would have seemed equally extraordinary that many of the Red Guard thugs, who had terrorized their compatriots and destroyed a huge amount of an extraordinarily rich patrimony would become university graduates, fluent in a foreign language, a mere decade after the change in regime, with their kids studying abroad, listening to western music, watching foreign movies, using Apple products and becoming the largest consumers of many European luxury products! It would have seemed equally extraordinary that a rampant growth in population could have been brought under control, that starvation greatly diminished, basic functional healthcare established throughout most of the country and that China would completely overshadow the rest of the world in terms of infrastructure development.

And crucial elements remain from the times of the Red Guard. On the one hand, during that period the Red Guard was ‘programmed’ to challenge and destroy the previous educational system and values, tasks at which they were highly successful. On the other hand, for those living under the Red Guard, survival was goal number one, through awareness, cunning, resourcefulness or whatever it took! And, for those who survived the regime, these ‘skills’ have not been lost under today’s much freer and more benign politics. This has left a country, where the value system had been based around a Confucian ideal rather than an enforced religious doctrine, without any real historic values and with very few in a position to pass on what might remain of them. The country seems largely composed of ‘survivors’ without a clear moral compass, a whole new generation without mentors to establish the basic values of what is right and what is wrong and opportunists (either of Chinese heritage or not) entering simply to take advantage of an economically appealing situation. Much has been said about the shortcomings of China’s implementation of a legal system; yet, the most effective legal systems require some underlying moral code for them to gain any form of real traction and one of the biggest concerns over the next three decades is whether anyone actually will believe in the system. Although many of us in the western world might not be active participants in a religion, most still retain some affiliation and are at least influenced by the concepts of guilt and the ‘potential’ for consequences of today’s actions in the hereafter. In practical terms, the Chinese revolve much more around ‘face’, how one is perceived today. As such the moral underpinning is simply not to be caught or exposed! Power and influence provide tremendous shields and those who benefit from these are quite naturally rather resistant to losing them. This makes practical application of the legal system very difficult. Furthermore, until recently, judges were primarily former army officials with little legal training – their main qualification being card-carrying members of the Communist Party. The bias to protecting the interests of the Party and those affiliated remains a major stumbling block to an even-handed and properly implemented legal system.

It is with these immense macro elements in mind that one must evaluate China today. Those on the glass half empty side, are often fully justified in their concerns/criticisms; and, in my opinion, the willingness of dissenters to push the envelope and challenge the Administration will be a crucial element to establishing an appropriate balance and thereby maximizing future gains for the country. Yet, given the unbelievable amount of change that has occurred and the pace at which it continues to happen, it is unrealistic to expect everything to move smoothly and without problems and setbacks. Stay tuned for an exploration of many of the constraints currently facing leadership in Beijing and around the country.

Internal and External issues confronting China’s leadership

INTERNAL

Power battle/Internecine political strife. No country glides by without battles for internal control. The U.S. is engaged in a take-no-hostages, bare-fisted brawl between Republicans and Democrats, without even a clear, definable agenda on either side. And this exists within one of the most transparent political systems in the world. China has always been a manifest example of the iron fist – sometimes with a velvet glove, other times without. The prize from control is a level of nepotism only imagined in most developed countries. The level of privilege accorded in the past to those with power was extraordinary; this remains the case today; but, instead of representing merely a differentiated way of life, it now translates into virtually unlimited material wealth, both domestically within China and exported surreptitiously (but in plain site) to investment havens around the world. Often the father has the power, but does not actually personally realize financial gains; his wife, children and relatives are those who accumulate the wealth. The battle is being fought on many dimensions, but the two major ones, unsurprisingly, are for control and for ideology. Although personal advancement remains virtually ubiquitous as a motivation, there do remain ideologues who genuinely see rampant capitalism as an evil approach, a viewpoint that certainly can be substantiated by many data points not only abroad, but at home over the past couple of decades. The movement towards socialism/communism, as a reaction to repression and concentration of wealth, education and control, is understandable and even laudable; its appalling implementation is less to be commended. Yet, there remain vast income, wealth, education and power disparities in the current quasi-capitalist approach, that leaves the door open for many ‘old school’ participants, who either remain ideologically pure or merely see forceful upholding of socialist principals as the most expedient approach for regaining/retaining power. At either ideological extreme, the risk of social unrest is extremely high and this remains a major area of concern for the current regime. Progress and political survival depends on carefully avoiding excess displays of rebellion on one side and suppression on the other.

Corruption. This could be a significant detractor to long-term development, while it is a crucial tool for the regime to achieve shorter-term goals. This is discussed at more length later in the letter.

Labor. The primary element that has allowed China to explode onto the world stage has been its seemingly endless labor pool at costs hard to beat or equal and limited ‘restrictions’ on use (e.g. number of hours worked, work conditions, exposure to toxicity, etc.) The movement, particularly in the southeast of workers from the farm to cities has to date been able to feed the demand, particularly with easy access to ports. Now capacity is straining and Beijing is trying to address a number of issues simultaneously:

- There are now periodic shortages of labor in cities with large manufacturing facilities.

- The increased cost of living has put a strain on workers and has led to increasing worker demands.

- More open media and internet has made workers more aware of their own condition.

This is leading to pressure to increase prices, something that Beijing is hesitant to do, given the need to keep people employed and the price elasticity of demand for the products they produce, particularly given labor competition from Vietnam, Cambodia, Bangladesh, etc. In order to provide more labor supply and also to better distribute industrialization across the country, there has been a huge effort to improve infrastructure in many inland provinces. However aggressive the effort, it does take time to build roads, railways, airports, housing, schools, hospitals, etc. And, as the clock ticks, there is no question the government is sensitive to potential for mass disruption if employment is not only maintained but improved.

Ethnic diversity/control. Unlike the United States that effectively has two borders (three if one includes Alaska’s proximity to Russia) – a large, under-populated and much aligned neighbor to the north in Canada and a relatively short frontage with a relatively weak and disorganized nation to the south – China borders 14 countries (the most of any country in the world), many of them volatile, including Russia, India, Pakistan and North Korea! Within the country there are 56 recognized ethnic groups, speaking a total of 292 living languages (Jurchen being the 293rd, but officially extinct)! Outside of very culturally distinct provinces there are five autonomous regions (Tibet being the most externally known) that represent 45% of the landmass of China! Although the Han Chinese comprise more than 90% of the population, the other 55 ethnic groups make up a population of significantly more than 100 million people. Perhaps managing this is not as intractable a task as in India, but it is certainly not a walk in the park! Under a regime with very strict controls and a limited telecommunications infrastructure, keeping order was largely feasible. In an atmosphere of liberalization, with ever less controllable sources of information, the government has a rather more complicated job.

Income disparity. This is an issue confronting most of the world, as a growing number of those at the top get more and more relative to those at the bottom. Perhaps this is merely a perception issue (with income disparity always extreme), as media has made the availability and dissemination of this type of information much more common. Historically, countries like China had particularly limited media, largely controlled, low levels of literacy among the poorest and strong governmental control. Furthermore, with survival the biggest concern among the poorest, focus on wealth disparity as an issue rarely surfaced. With China’s massive leap forward, through industrialization, urbanization, national wealth creation and increased information flow, the debate on the wealth of the richest and the hardships of the poorest is becoming more active and, given the size and dispersion of the population, is one of the governments most intractable issues. Growth rates in China, together with RMB exchange rates are an important issue for the U.S. and other countries, but for Beijing they are pivotal and central to policy decisions that are contemplated and enacted.

Controlling urbanization. Taking city dwellers to the provinces for socialist re-education seems a rather distant relic, as the flood of migrants to urban areas increases. In 1980, approximately 20% lived in cities, today it is about 50% and continues to grow. By 2025 it is estimated in China there will be 221 cities with more than one million inhabitants – there are nine in the U.S. today! The reasons are varied, but grounded in the improved efficiency of an agricultural sector that can better support an urban population, the continued perceived (and actual) massive disparity in quality of life between cities and poor rural areas and an increase in awareness through media and telecommunications. This flood of rural poor into cities is common to most emerging nations, but is rarely particularly well handled. The mega-cities that have spawned around the world – Mumbai, Sao Paolo, Mexico City, Cairo, Johannesburg, etc. – have huge festering slums and infrastructure not nearly sufficient to meet even basic needs for many of their residents. Officials in Beijing and around China are more than aware of this and do make efforts on both major infrastructure programs and also on controlling the flow of rural workers into cities. China has seen particularly large growth to its coastal regions – as a result of its creation of special economic zones to address the surge in production for global trade; however, much of the population lives elsewhere and the government has been making efforts to grow cities in other parts of the nation. However, for this to be successful, transportation and related infrastructure is necessary; hence the vast spending on highway, rail, ports and air hubs. China, more than most other countries, has mechanisms in place to control the flow of population. Their Hukou system, which requires individuals to obtain special permits to officially relocate to a new place on a permanent basis, are relatively effective over the longer term. Under Mao, violations to sanctioned movements were frequently dealt with in the harshest terms; today, it is dealt with economically, through limiting access to housing, education, etc. Only those with the proper permits need apply. Naturally, the system is imperfect, the ‘floating population’ is estimated at more than 200 million, and the country’s corruption infrastructure has mushroomed. Although the existence of the system is now a topic of debate, particularly outside of China, the liberalization trend is meaningful and the results relative to other rapidly evolving nations are certainly strong.

Population size/growth/aging. China competes with India for the title of the world’s most populous nation. This has both negatives and positives and represents opportunities and threats. Current population is estimated at slightly more than 1.3 billion, up from 563 million in 1950, but slowing. The birth rate is about 1.7, which is below long-term sustainable levels of 2.1, but still represents slight current growth, as a result of improved healthcare and some immigration. Much of this has to do with the highly publicized one child policy and the more benign realities of urbanization and broader education. Population is expected to peak in around 2030 and then slowly decline (thereby giving the population title to India, that is less organized in its approach to growth). No matter how one looks at it, this is a huge number, requiring massive logistics to deal with food, shelter, education, healthcare, transportation and growing consumer needs. Balancing the size of the total population against the composition of the population will be one of China’s bigger problems going forward. For the moment, however, it appears the more immediate issues are being tackled first. Nonetheless, everyone is aware there are basically no pensions and little confidence there will be in the foreseeable future; as such making money here and now is particularly important.

Infrastructure Development. For a diverse set of reasons, both obvious and more subtle, and clearly not directly applicable to this discussion piece, the period under Mao saw little on the front of infrastructure evolution; in fact, it saw mainly a combination of decay and actual active destruction. With the shift in policy away from radical ideologically-driven communism towards a more market aware culture, with a clear goal of decreasing the crushing poverty of the rural peasantry and the stagnant quagmire of urban life, a clear decision was made to increase productivity. This naturally involved an extremely broad-ranging set of agendas, ranging from improved food production, reconstitution of SOE’s (State-Owned Enterprises), improved financial system, etc. However, a common obstacle to almost all other policies, was a crumbling or often non-existing infrastructure. It is the curse of most emerging nations (and, frankly, many developed ones). Chinese leadership made infrastructure development a core and pivotal element in their move forward. This has entailed an across-the-board sprint in every imaginable sphere: roads, ports, railways, airports, energy, water distribution, urban renewal, agriculture, hospitals, schools, etc. China rapidly has become the largest consumer of steel. The same has been true for a wide range of commodities, making China the pivotal price setter, thereby influencing much of world supply and demand and thereby becoming an important factor for consideration in the policies of other major governments around the world. At home, one of the biggest potential drawbacks in the frenetic pace of this development is that it represents one of the largest ‘land grabs’ in history, with corruption playing a part in virtually every facet of any project. Continued unabated, this is most likely to lead to an extensive range of highly unprofitable projects, often with corners cut that might detract from their longevity/sustainability and also might result in undesirable shorter term disasters – the recent high-speed train accident being a case in point.

Energy. China is by far the largest producer and consumer of coal in the world. Having been a major exporter, it is now heading towards being a net importer of the commodity. This dependence on coal is the primary reason China is the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases (not per capita, but in total). Oil use has also increased dramatically, as has natural gas. Other sources such as hydro-electric, wind and solar are growing significantly, but (as in the United States) represent a very small percentage of total use. Plans for nuclear expansion were curtailed post Fukishima. Although, per capita, significantly behind the U.S. and other developed nations in energy consumption, the rapid pace of industrialization will continue to necessitate heavy production and imports of energy. Securing sources is of key strategic importance to the Central government. Although the only emerging nation to have a meaningful policy and position on global warming, this is unlikely to have a major impact over the short-term on real policy decisions.

Food production. China has a relatively small amount of arable land per capita, making efficiency key to supporting the country’s food needs. When the Communist Party prevailed in the Civil War, it confiscated land from landlords and redistributed it to 300 million peasants; this ownership structure, however, was short-lived, as the Party gradually created collectives and then as part of the ‘Great Leap Forward’, into communes, where private food production was prohibited. This was largely responsible for the Great Famine, but the communal system remained in place until the early 1980’s when, under the ‘Four Modernizations’ regime, ownership was gradually given back to individuals. Strict quota systems and artificial price setting mitigated improvements, but since 1993, when these were relaxed, 90% of annual agricultural production (according to Wikipedia) is now sold at market prices. China’s focus on irrigation projects, including the massive Three Gorges Dam, has also led to significant improvements.

The overall picture, however, is not all positive. China remains very susceptible to Mother Nature, particularly to drought. When there is insufficient rain/snow, there is now the possibility of releasing vast amounts of water from dammed reservoirs; however, this then leads to potentially diminished hydro-electric power – thereby impinging on another of China’s crucial needs for development and stability. Furthermore, aggressive farming techniques, including the use of harsh chemicals is leading to a diminution soil quality that could lower future acreage and yield. Also, toxicity levels in agricultural production are of growing concern. In the short to medium term these issues are likely to worsen.

As an additional current problem, although marked improvements have been made to the country’s, physical infrastructure, there are still severe food distribution issues. Some of these are caused not just by poor transportation, but by lack of sophistication in marrying supply and demand and in managing logistics. The good news on this front is that many of the problems can and will be addressed, thereby improving consumable output numbers over the medium term.

Water and Air . China faces water issues, not just for agriculture, but also for consumption and industry as well. The battle operates in three-dimensional space: quantity; quality; and cost. As discussed above, the quantity issue remains a problem (e.g. Beijing water reserves are down by as much as 70% in the last five years) and, as in many other countries (the U.S. included), there are massive battles as to the best use, with massive economic motivation by many individuals to resist ‘best use’ approaches. China’s situation is exacerbated by still limited (though improving) wastewater treatment and by what is generally acknowledged as potentially crippling levels of increased industrial and agricultural water pollution. These are not surprising, given the rapid level of industrialization and increased GDP per capita, but given the size of the country and its population, the issues are gargantuan. From the rest of the world’s perspective, they are also very problematic, as pollution represents one of the least desirable Chinese exports. Coastal China does have the ability to build massive desalinization plants, but the costs – although decreasing – still remain very high and the process is normally very energy intensive.

Air pollution is ubiquitous and highly visible. In major cities, the air is literally so thick you could cut it with a knife. On a moderately bad day in Beijing, it smells and feels as if tires are being burned on every street corner! According to the World Bank this leads to hundreds of thousands of premature deaths a year, primarily from cancer and cardiovascular disease. Once again, the problem is not unique to China, but its vast increase in industrial production and energy use makes it the world’s number one pollution concern. The government is addressing the problem, but is caught in a no-win situation for the foreseeable future.

Control of Information. Although the government still exerts strong control over traditional forms of media and education and for the moment on social media and the internet as well, the latter are of major concern, as they are almost impossible to fully control let alone extirpate. The ineluctable progress of technology will almost certainly provide a forum for discussion that might be at odds with government policy. In the meantime, the central government is not only looking at how to stop others from using the internet and technology, it is conducting aggressive programs (domestically and apparently internationally), both overtly and covertly, to collect information and aid in implementing policy objectives. How Beijing handles the balance of defence and offence will be very interesting to see. With the clear recent history and mixed (largely negative) results of the Arab Spring, the Party has much to be concerned about and deal with.

EXTERNAL ISSUES

Borders. Along with Russia, China has one of the two longest land borders in the world (who wins depends on the sources used). In any case, having 14 neighbours presents a real challenge and this does not include traditional rivals such as Japan and now, with territorial disputes, South Korea as well. The geography and topography is very diverse and national security remains a key concern to leadership. This is exacerbated by China’s internal ethnic diversity and the worry that externally generated conflict might have rapid internal contagion. Although the size of the People’s Liberation Army has been decreased, it is still the world’s largest army at around three million, with a standing army of approximately 2.25 million. Although certainly not the most modern, a considerable amount has been spent to modernize the force, its technology and its equipment. What is extraordinary, however, are the 600+ million men and women defined as ‘fit for military service’! China’s active growth of its maritime and air forces, together with a focus on sophisticated weaponry and growing financial strength puts China front and center in terms of future global balance of power.

Use of Military. Although included in the external section, there are many uses of military, not all outward facing. The four most important are:

- Maintaining internal order. Because of the quilt-work of cultures and ethnicities that has comprised China for so many centuries, the military’s greatest function throughout most of history has been to establish/maintain cohesion within the country’s borders. This has often been extremely brutal. Today, the army remains a visible presence and its current role seems more to represent a threat of suppression, although that does not mean it is not used when deemed necessary.

- Defense. This is a broad term that often masks preparation for hostile activity. Nonetheless, over the course of history, no major nation has survived long periods without a strong defensive force. China has engaged in many tactics over time, including building the Great Wall, introducing cavalry, developing gunpowder, etc. With the country’s growing prosperity, China’s military stands to benefit materially. The efficacy of the force depends on many factors. The PLA’s greatest function for a long period of time was to preserve the ideological purity of Mao’s communism. With the cooperation of the Soviet Union, the army started to shift towards better organization and function, but ideology prevailed and relations with the USSR declined. More recently the move has been to downplay the heavy-handed use of military to enforce political viewpoints. However, the generation of hard-line ideologues is not yet extinct and some risk remains of a reversion. It is too early to tell with the new regime, where the balance will lie. Nonetheless, for a country where signalling is often as important as action, it is interesting to note that the lyrics of the national anthem remain:

Arise, ye who refuse to be slaves;

With our very flesh and blood

Let us build our new Great Wall!

The peoples of China are in the most critical time,

Everybody must roar his defiance.

Arise! Arise! Arise!

Millions of hearts with one mind,

Brave the enemy’s gunfire,

March on!

Brave the enemy’s gunfire,

March on!

March on!

March on, on! - Means of strategic and tactical expansion. Given the length of China’s history and the military and organizational prowess it has demonstrated at different times, China has been relatively non-expansionist (do not tell this to the Tibetans and other absorbed regions). At different times, it has absorbed new territories, but it appears that most of its military efforts have been in keeping these, rather than in using them as steppingstones towards global hegemony. During the post-WW2 period, China was very active in supporting communist governments throughout Indochina. This can be construed either as expansionist, or as defensive against the encroachment of traditional Western powers. China’s support of North Korea today is an interesting vestige of that era – reading the tealeaves of their interaction there is important to understanding their policy direction. Regardless, China is entering a period of potentially great prosperity. This will allow for considerable incremental spending on military activities. Under relatively benign leadership, this is not necessarily a direct external threat; however regimes evolve and leaders change…

- Preservation of interests outside one’s borders. With China’s increased global trade, increasing dependency on foreign resources and foreign ownership, it would be naïve to believe there will not be a concomitant increase in paramilitary/military presence in areas of strategic importance to them. This has certainly been the case over the centuries, whether Roman armies, Hun hordes, European colonial powers or U.S. capitalists. It is a matter of necessity to preserve self-interest. Although China has virtually no permanent bases abroad, they have expanded their navy (although still not a global threat) and they have deployed paramilitary forces to protect interests in Africa and Latin America. As they continue to bring cash into the licit and illicit economies of many emerging (or static) nations, their influence is likely to increase dramatically.

Regional relationships. China has had tenuous relationships with many of its direct and regional neighbors. Prior conflicts with Russia (and its satellites), Japan, Korea, etc. and strains with India, Pakistan, etc., put Beijing in an interesting position. China’s economic growth has been a boon for the region and has resulted in economic stimulus for many countries, yet the level of mutual trust remains low. Ongoing territorial disputes (for seemingly incidental islands) and military confrontations have raised regional tensions. Coupled with an understandable unease with Russia and the potential of a longer-term conflict with the other major population base (India), Beijing has an interesting set of dilemmas. This is exacerbated by the country’s interactions with Western powers that still have disproportionate control of global economics and politics. Balancing the short-term need for strong economic growth, with longer term planning issues, is something that a single-party centralized government is better positioned to do than most. Yet, there is no easy solution, as outcomes are extremely path-dependent and even short-term politics around the globe are very hard to read.

Economic Role in the World. China has made the transition away from a country with virtually no global economic footprint or impact (outside of its long-entrenched emigrated diaspora) and yet an important role as a major international security threat. It is now the world’s most potent growth engine, a crucial trading partner for developed and emerging nations alike, and an apparently more benign (perhaps simply less overtly threatening) military power. It has sought to distance itself from economic programs that proved to be disastrously ineffective and has been willing to adopt much of the machinery of market-driven economies; yet, it has not completely disavowed its recent Communist ideological roots. Without experiencing a complete train wreck, it is hard to imagine China not increasing in economic and political importance. The mere virtuous impact of positive compounding from a low base – a country with a large population of seemingly avid consumers and a political thrust moving to satisfy/mollify this massive constituent base – virtually guarantees a mushrooming balance sheet and its accompanying benefits and woes.

As the world’s second largest exporter of credit (after Japan) and growing, China’s Treasury and economic policies hold tremendous importance around the globe. A decision to limit, maintain or increase U.S. Treasury holdings, impacts both China’s economy, that of the U.S. and of those countries with currencies pegged to the $U.S. or inextricably economically linked. As the world’s largest single exporting nation (the E.U. in aggregate is still slightly larger), where the RMB is set and the levels of interest rates are of high importance. With exports running at more than 30% of GDP and a large remaining agricultural sector, China remains both economically and politically dependent on the health of its trading partners. That China has achieved what it has is extraordinary, particularly coming from an atrophied, decayed and corrupt base, with a highly xenophobic past leadership. Big problems remain in a corrupt political system, an unevolved banking/financial sector, an under-tested legal system and a still large protected group of SOE’s. Commentators split on whether these deficiencies will cause major delays in China’s upward progression – personally, I see them more as a tropical depression than a full-fledged typhoon!

HOW THE CURRENT POLITICAL SYSTEM ACTUALLY WORKS

The first thing one needs to internalize is that China does not operate by the same rules as most developed nations. The overarching reality is that democracy is neither a short nor longer-term goal within China. The paradigm is completely different from those of the U.S. or even more socially democratic governments in Europe and elsewhere around the globe. For China, the political system is merely the mechanism towards a defined set of goals that are set not by popular demand, but by the Select few at the top, through a byzantine and very secretive process (that may or may not be for the good of society and the country). The benefits are that change is easier to enact – to the extent it is expedient to allow more popular input (as at present), so be it; when the converse is true, the power structure is designed to allow for dramatic reversals. The risks are that in the wrong hands, bad policy and bad decisions can be enforced without recourse. The culture is different. It is next to impossible even for local Chinese to effectively read the tealeaves. There are rarely ‘winds of change’, more like subtle breezes that confound even local political meteorologists. As a foreigner, particularly an American, interpreting a conversation can be very difficult, let alone understanding the overall context. Spoken words are not intended to be taken as literal. The American approach of ‘I say what I mean and I mean what I say’ is simply not part of the cultural paradigm – for better or for worse. In fact, it is generally considered uncultured, uneducated and/or just plain rude to be direct. In Mandarin, the use of different tonal pronunciation of the same word, generates different meanings; and the language is a fine metaphor for the culture behind it. Subtlety and circularity are inalienable parts of life in China. Understanding cultural differences is paramount. The Chinese culture embraces superstition, with numbers being lucky or unlucky; similarly, colors are very important symbols. A complete understanding, as a foreigner, is rather problematic. So where to start? First, understand how the political system is set up, at face value, and where power lies. Although this is very complicated in most countries, it is even more so in China. Before explaining why, let me simply provide an outline, from the bottom up.

- There are five levels of local government hierarchy (four official): (i) the village, not a sanctioned part of the system; (ii) the township; (iii) the county; (iv) the Prefecture or Municipality; and, (v) the Province.

- At each of the four official levels, there are both elected officials and a member of the Communist Party who share the power. Not only does the Communist Party official have precedence, most of the elected were carefully screened as candidates by the Party – after all, why leave anything to chance! Needless to say, loyalty not merit is the key consideration.

- In Autonomous Regions there is a symbolic show of sensitivity to the local ethnic group. In reality, there is then an even more authoritative Party member.

- There is a tiered system, with local officials elected directly by the populace to the People’s Council; the People’s Council then votes members onto the People’s Provincial Council and members of the Provincial Council vote for members of the National People’s Council that congregates annually in Beijing.

- Responsibility for each key functional area is shared between an official at that level of government and his/her equivalent at the next higher level of government. This is meant to act to provide a cogent hierarchy, an effective level of oversight (control) from the top and to limit the amount of ‘slippage. In reality it can create more opportunities for subterfuge and certainly will often result in decreased efficiency in decision making and implementation.

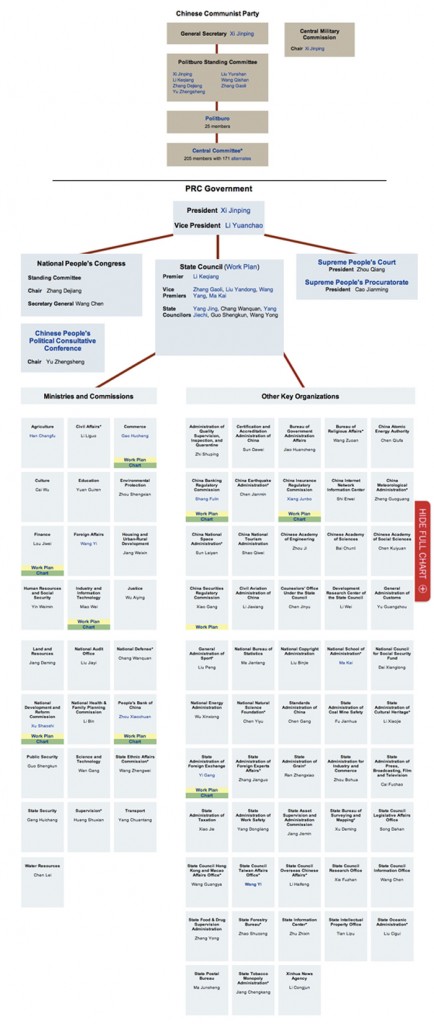

- In Beijing, power-central, the game becomes even more complicated. Power is supposed to be shared among the President, The State Council (composed of Vice Premiers (4), State Councillors (5) (same status as VP’s), and 29 Ministers and Heads of Commissions and the supposedly supreme National People’s Congress. Although no longer a pure rubber stamp, policy is generally conceptualized by the State Council under the leadership of the President. And yet, because there has not been a ‘strong’ leader, there has ended up being a huge amount of ‘horse trading’, leading to ‘consensus’ policies rather than autocratic ones. Ironically, the last strong leader was Deng who never officially occupied the top official positions.

- And then there is the Communist Party, with its own structure and hierarchy. The Party is led by the General Secretary, who is the most important person in China. Next comes the Politburo, consisting of 22 members of which the Standing Committee of 7 is the most important. Under them is the Central Committee of 205 members and 171 alternates. Alongside is the Secretariat, responsible for the bureaucracy that is a fief of the General Secretary. In order to assure Party control, the General Secretary is also the President.

- The military is supposed to be jointly governed by the Central Military Commission of the State and of the Communist Party, but the CMC of the State is rigidly screened to make sure the right candidates are on board, thereby ensuring full Party control. The head of the military is also likely to be the President and General Secretary. The following chart from the U.S.- China Business Council from PRC government websites, doesn’t even show a State CMC.

- There is a legal system that has been evolving since 1980. It is more developed on the criminal side than the civil, but is still in its early gestational period and its enforcement is uneven. Although the headline is that, as it strengthens, its independence provides a counterbalance to existing power structures, the laws are essentially designed and changed by Party leaders and functionaries and, therefore, are more likely to further enhance Party influence. Essentially, the Party is above the law and, therefore, if Party interests are at stake, the law is unlikely to be implemented. This makes the odds of foreign companies prevailing against SOE’s rather low.(Click the chart to view via US China Business Council)

The system is essentially a ‘super-matrix’ that tries to balance/organize the following:

- Centralized power and regional control at different levels, with little cooperation among the provinces

- Bureaucracy and political function

- Communist Party and ‘secular’ power

As indicated above, it is insanely complicated to understand how the structure works in concept, let alone to trans- or circumnavigate it. Things become wildly more difficult, when practical realities are brought to bear. Even if the structure were sound in its overarching goals, China has a huge impediment to execution as a result of major and minor power struggles and ubiquitous corruption. There has been an explicit policy and vigorous hand-wrenching over the problems of corruption, but tacitly it is accepted and in some ways even encouraged. Exceptions like Bo Xilai are publicly excoriated and dealt with, but otherwise it remains the same old same old. The new regime has made even stronger statements that have had the short-term impact of diminishing public displays of potentially illicit lavishness, but no skeptics really anticipate a major change – for all sorts of reasons outlined below.

Entrenchment is always problematic to extirpate, particularly when the benefits are most endemic to those charged with the task! More importantly, I am of the opinion that corruption is one of the major longer-term insurance policies leaders in Beijing are using to retain control. Throughout the Mao Dynasty, control was maintained through having an extraordinary information network on all citizens, through all sorts of means – neighborhood councils, spies, etc. Aggregation and control of records of activities allowed for complete control. It is hard to imagine the infrastructure for this system has disappeared completely – perhaps its function has simply changed! Without inordinate cynicism, consider that Beijing has actively supported the creation of a well-designed criminal legal system, but has chosen not to apply consistently. At the same time, the means of corruption have remained easily accessible to officials throughout the country; it is not hard to believe that detailed records have been kept of wealth accumulated by these officials and their families. As such, under current laws, a virtual army of politicians and bureaucrats are actually known to be guilty of crimes and they are fully aware their activities have been monitored. What better way to ensure compliance to the Party line! To the extent they do not challenge doctrine from Beijing or become an inordinate embarrassment, they continue to enjoy privilege and wealth. Were they to dissent, it is easy to bring them to trial and in a public fashion, without a kangaroo court, find them guilty of crimes they have actually committed (in this way China’s hold on power is far more subtle and sophisticated than the old-style Soviet approach still in fashion in Russia). To eliminate the means for officials to tap into vast unofficial wealth would, in fact, entail eliminating a crucial tool in centralized control.

Given this premise, it is important to understand the four primary types of corruption in China. Using Wikipedia as a source, I will summarize:

- Pure graft. This is the most bare-knuckled form and manifests itself in direct bribery, illicit kickbacks, embezzlement and pure theft of public funds.

- Rent seeking. This involves using monopolistic power to directly sell or receive ancillary benefits from providing use of some of these powers to commercial users (e.g. real estate developers being awarded government contracts or receiving public lands at below-market prices).

- Prebendalism. Using the power of one’s office to gain special privileges, benefits, deals, etc. This area has been so prevalent, that until recently, there was an almost acceptable ‘price list’ to have a meeting with a public official. Depending on the rank, the level of gift varied; for example, meeting with a junior official might require a bottle of Lafite Rothschild, whereas a session with a more senior official could entail a Rolex watch or a Louis Vuitton handbag for his wife. This can escalate into foreign travel junkets for officials and their families and extend into paid education for children at home or abroad.

- Misallocation of public funds. Many officials use the public coffers as a means to live a lavish lifestyle (houses, banquets, staff, etc.) on the government’s budget.

As you can see, these broad categories permeate every part of daily life and particularly the effective execution of business. It would be easy to go bankrupt simply greasing the palms of all those who might be useful or who pretend they might be useful. The problem lies on a range of different fronts:

- It is illegal for corporations based in the U.S. or with listings in the U.S. and those based in many other countries to pay bribes, although the line between a nice meal and one with a 1961 Lafite is often hard to define.

- Enforcement by the U.S. and other countries has stepped up dramatically.

- It is illegal under Chinese law to pay bribes in China.

- To the extent you are comfortable sweeping laws and morals under the carpet, it is often difficult to understand which bribes are going to be useful.

- As a foreigner, the risk is always high that a bribe not only doesn’t work, but might even backfire and be used against you!

Understanding how to navigate the Chinese society, business mores and political corridors is possibly the most complicated and important factor in engaging successfully on any front in China. The level of gamesmanship is simply much higher in China than it would be in most other countries. You are safest to assume you are always playing a multi-dimensional chess game, spotting your opponent a rook, a knight and a bishop; remember, just because you aren’t paranoid, doesn’t mean they aren’t out to get you. As such, a major problem is rarely even being aware of what you don’t know. It is almost critical to have a ‘guide’ to help find a reasonable path; but how do you determine whom to trust? And if you do find the right partner or advisor, the risks still remain high. Even the best laid out plans are much more subject, in China, to unknown, indeterminable tail risks. The bottom line, is the bottom line must be sufficiently attractive to compensate for the panoply of incremental risks. So, given the clearly uneven playing field, political quagmire, cultural differences and un-measurable risks, how can one improve one’s odds of success? First, please understand that as in any gambling endeavour, there are few guarantees. The question is often asked whether the risks are the same for large multi-nationals as for more modest entrepreneurs and those in between. In some ways the larger you are the more you can gloss over, sweep under the carpet or simply power through; however, as BP learned in Russia, the bigger you are the harder you fall. An unenforced legal system has the risk of hurting anyone.

As such, here are a few practical steps you might consider:

- Truly understand as much about China as you can before you start. Remember Shanghai and Beijing are not China, the same way that New York is not the U.S. You must explore outside your comfort zone to figure out whether you and your organization have the stomach to operate sustainably in the country.

- Determine who from your company wants to be in charge of the project or business. Does he/she like China and the Chinese and be willing to live in China – if so, where? Will the family move over? Are they well suited to the lifestyle? Unhappy team members are less likely to have the appropriate focus.

- As a corollary, understand which employees will be able to best understand the subtleties of the culture and system, while not succumbing to its temptations.

- Determine whether there are global legal, accounting or consulting firms (that fit into your budget) who have had significant failures and successes in China who can help you from having to reinvent the wheel.

- Understand that trust is a very ‘flexible’ concept and (as discussed earlier) the foundations of ethics stem from different sources and are applied differently. Always start suspicious, but do so without being aggressive or showing your hand. Build trust over time, but remember, it will rarely be safe to lower your guard.

- Having said this, spend considerable time and effort upfront to research and find someone you believe you trust more, who has experience in your business/project area, who is local, speaks the language in the local dialect and is aware of the political landscape. Finding a local JV partner might be more effective for achieving short-term progress and goals, but comes with the inevitability that over time goals and implementation methods might diverge greatly and when they do, you are unlikely to have the upper hand.

- With your local advisor, figure out those in power who can help/hinder your project and who might gain/lose from seeing it succeed.

- If you have local operating or financial partners, find out how well connected they are. Understanding who they are and how they have done business is crucial. Take no representation at face value – verify, verify, verify. To the extent their ‘references’ do check out, to the best of your knowledge – do these represent incremental safety to you (i.e. will they be able to shield your business from outside interference and/or be able to access favorable treatment)? Conversely, will their relationships protect them in the event of some dispute?

- Determine whether or not it is feasible, given legal and moral constraints to attract the right support and/or deter those antipathetic to your endeavour.

- Figure out who your current competition is and who might enter the fray over time; most importantly, determine who might ‘support’ them and how strong they might be.

- Determine whether, if you are successful, you are likely to become overly desirable and if so, who are the likely players to enter the game, whether they might have an unfair advantage and what you might do to block them or make them part of your team.

- If you have proprietary Intellectual Property or advantageous process or branding, understand whether you will be able to protect them, both from your enemies and your ‘friends’. Do everything you can up-front, such as re-registering all key company and product names in China, including all possibly closely related Chinese names.

- If a major capital investment is required, can you finance it locally (on advantageous terms) so that both your assets and liabilities are within China? This might partially level the playing field.

- If your investment requires the acquisition of real property, determine to the best of your knowledge whether you have clear title, and even if you do, what you can do to protect yourself against eminent domain or the simple private rapacity of those in positions of power. Although this is unlikely to happen explicitly at the highest echelons in the capital, the local fiefs around the country can get away with untold amounts.

- Will you have control of or access to the full accounting and cash flow chain? The probability of monies finding unexpected homes, increases dramatically the further you sit from the cash register – and China is quite distant from the seats of most Western companies. Conversely, the closer you sit, the less protection you have if some of those funds need to be paid for ‘unconventional consulting’ services.

- Carefully evaluate how you look to repatriate cash flow streams. Getting funds out of China can be problematic. Although this has eased to some degree, one does remain at the mercy of the current regime – either bluntly in terms of interdictions, or more subtly (as occurs around the world) in the form of taxation, fees and currency regulation.

- If you intend to keep monies local, carefully understand the implications of not hedging the currency and the costs of doing so.

- Carefully establish exit strategies up front and constantly review whether or not they remain feasible.

- Never take anything at face value or for granted. It is not that opportunities are not plentiful, merely they will often have unanticipated facets that might complicate your life.

OVERALL CONCLUSIONS

There are no easy conclusions to draw. China is just entering a new ten-year leadership process and the dust behind the scenes is far from settling. As discussed above, the level of politics is extraordinarily high – apparently making the Vatican seem like child’s play! The stakes are vertiginous, both for the country and personally for the individuals who have/gain/lose control. It will take at least a couple of years for an effective transition to take place and even longer for anyone to have a good shot at interpreting the tealeaves. As such, this piece has not tried to predict political action, more to reflect on the political and practical realities facing China and those interacting with the country.

The distance covered in a mere three decades is almost beyond comprehension. The level of change has been enormous and continues apace. However, the acceleration (the second derivative) that has been achieved is difficult to see continuing. This does not mean there will not be massive change and progress going forward, it just means that one cannot extrapolate past results in a formulaic way into the future. It is much easier to achieve 100% growth on a small denominator; as the base grows, achieving similar future growth becomes challenging at best – please refer to Apple Computers! The question as to whether China will become the world’s dominant super-power is one well worth contemplating. That this is a foregone conclusion is far from certain. That the country has achieved a three-decade period of enormous success and progress is undeniable. Watching China become a power player on the global stage is one thing – seeing it take the mantle of leadership is another. With its population base and growing wealth, it is positioned well to benefit from a virtuous cycle – growth creates more wealth that is then recycled back into the economy or into productive international investments, that then cause further growth, allowing for more infrastructure, educational, healthcare growth, and so on. Knowing how to use these to maintain internal stability, evolve the political, economic and social system and take power away from the entrenched developed nations requires a different set of skills and resolve.

To date, China has had the blessing of not being ‘encumbered’ by democracy. No matter how cumbersome it might have been to achieve a consensus among the power elite, there has not been the concern of voter approval or true judicial oversight. Decisions have been and continue to be made and implemented, for better or worse with remarkable speed relative to other countries such as India or even the U.S. or Europe. When things work well and the ‘talent’ is good, that is hugely beneficial; unfortunately, the laws of regression to the mean apply in China as much as anywhere else and the risks of largely unbridled power can lead to very bad results as well. For China to be a welcomed and sustainable super-power (i.e. one not forced upon the scene by military might), it has the following challenges it needs to overcome:

- A judicial system that is perceived to be, and actually is, applied relatively fairly and evenly across all constituents, whether they be rich or poor, politically connected or not, Chinese or foreign. In the short-run, China has been able to skirt around the edges; over time, however, investors, institutions, employers, employees all need to feel they understand the rules of the game and that they have a fair chance of being protected and winning. Without that, the cost of investment will increase over time, lowering profitability, decreasing employment and the concomitant tax revenue and slowing growth.

- A liquid, diversified and well designed financial system. There need to be more sources of access to capital, both debt and equity and a system that protects all three constituents, owners, borrowers and lenders. Although the banking system has come a long way, it is still largely an arm of the Central Committee, without sufficient independence to assure smooth, uninterrupted functionality. A public debt market, equity markets with depth, breadth and liquidity, derivatives markets to allow for hedging are all necessary to allow for necessary flows of capital. Otherwise, there always looms the risk of lack of liquidity and the prospect of hugely inefficient and/or unwise allocations of resource.

- A system where access and success are not predicated virtually entirely on Guangxi. All countries have both explicit and implicit corruption (i.e. direct bribes and use of connections and influence). Unfortunately, it seems to be an inextricable part of human nature. In many countries, particularly developing ones, it is ubiquitous. Often it is a functional part of the system – the country has insufficient tax revenues to pay for all governmental and police functions, and therefore pays its civil servants a fraction of what they need to survive (let alone thrive), expecting the rest to be ‘made up’ in whatever ways are most expedient. Although generally undesirable, it is understandable in countries emerging from dire circumstances; for a country looking to be at the top of the food chain, it must be eliminated. However, for reasons discussed earlier, one of the major strategies for maintaining centralized power is a controlled dissemination of ‘privileges’, primarily the illicit aggregation of family wealth, by those needed to run key federal and local aspects of the country. Furthermore, 5,000 years of history are hard to change overnight. As such, it would be disingenuous to anticipate a major actual near-term shift in this area.

- A government that is not a question wrapped in a riddle packaged in an enigma. The use of stealth strategy, whether that is on the military, business or policy front can be very effective in the short run. However, over time, alliances based on real factual interchange and genuine serving of mutual interests becomes necessary. China’s continued use of ‘Oz’ behind the curtain and trade policies that are allowed to proceed only to pander to the basest level of consumer capitalism are, realistically, not sustainable. Unfortunately, given the opacity at every level of government, short-term change is also unlikely.

- A social structure that does not consistently feel it is teetering on the edge of morphing into something different, yet something that no one can anticipate. The U.S. ideal that China will wake up one day and suddenly agree that Western democracy is the divine preordained solution is both unrealistic and fundamentally flawed. China has a unique history and its ideal social paradigm for today has yet to evolve. However, as with the prior point, the obscurity in which major national decisions are made, creates a constant level of uncertainty, that is designed to keep any ‘opposition’ off balance, but which in fact has the long-term effect of destabilizing society. Unless Beijing chooses to revert to blatant nationwide military suppression of its population, there is a clear need to signal the pathway that has been chosen and then to implement it. The Chinese look more to results than anything else. These do not need to be democratically achieved, merely well developed, communicated and executed.

- A plan for how China’s growing military force will interact with the rest of the world. Although not the major concern of the U.S. and Europe to this point, China’s growing technological prowess and its means to support a vast standing military, is become one of the key geopolitical quandaries. There are many reasons to try to avoid Cold War types of battle lines, yet without meaningful and clear communication, the other current world powers will be left with little choice than to circle the wagons.

- An internal policy on resource distribution, education and social services that allows calm to prevail. The recent history of virtually total penury among most of the vast population remains vivid and alive. The maintaining of internal stability is key to any growth strategy; this, however, is easier said than done. It seems inevitable there will be lurches forward accompanied by frequent backsliding. The economics and politics surrounding these issues is enormous and will often lead to contentious and intractable situations. The increase in types and amount of media and non-government sanctioned communication/propaganda is enormous, and will make the unopposed implementation of policy virtually impossible.

- A policy for economic balance that is not subject to the vicissitudes of the economies of major trading partners. China is a potentially large enough economy to allow for a huge percentage of GDP to depend on domestic consumption. Getting to that point is extremely important, as the problems in the rest of the world are likely to lead to unpleasant periods of brinksmanship that, frankly, neither side can afford. China needs to refine its internal economic model sufficiently to protect itself, to a large extent, from external contagion. It is difficult, however, as consumption will be constrained by a high savings rate needed by individuals to compensate for no pension system or reliable healthcare.

Each of these points can be achieved to some extent; yet, none is easy, particularly in the short-term. Those who see the imminent demise of the current global status quo, dominated by current powers, are most likely plain wrong! That the balance of power is undergoing tectonic shifts is undeniable; however, the vast amount of amassed wealth and power of long-established (colonial) powers, will not evaporate overnight. It is important to understand both that those with an advantage will not cede without a struggle and that those trying to squeeze a century of development into three decades will not do so without interim setbacks, no matter how careful the thought and how punctilious the implementation.

The fact there remains so much uncertainty around China is part of the opportunity. There are certainly obvious areas of potential and, ironically, each area of major risk probably affords even more opportunities. The fact that China is large and growing and that it is moving from poor agrarian to sufficiently affluent urban is undeniable. This represents significant opportunity in every type of deliverable – housing, transportation, clothing, food, entertainment, travel, etc. However, as most of you reading this letter were not reared in the PRC during the Cultural Revolution, it is important to be particularly prudent in how you seek to take advantage of opportunities. China needs ongoing sources of outside capital and expertise and will promise whatever is necessary to entice them. The reality, however, is that China remains a State-tolerated ‘kleptocracy’ and the operative approach needs to be ‘caveat emptor/investor’! The legal system is there, but not necessarily there to protect the outsider, or even the local who does not have the right lineage or connections. Large discounts need also to be applied to any set of returns, given the potential for financial market manipulations and potential changes in liquidity, both regarding extracting capital from the country and also exchange rates. In China, a prudent investor must focus first on return OF capital, long before return ON capital. The new leadership has begun to signal very strongly that the policy of relative acceptance of both quotidian and massive scale corruption will end, but given the level of entrenchment and the benefits to those trying to retain power, it is hard to believe meaningful change will occur at any time soon.